Cheap thrills

Most motorcyclists know the old adage, “It’s more fun to go fast on a slow bike than slow on a fast bike,” or as one of my riding buddies says, “The smaller the bike, the bigger the grins.” These quips contain real truths about the joys delivered by many lightweight motorcycles, which often make up for their shortage of ponies with much maneuverability and user-friendliness. It’s also true bikes with modest power, low seats and unintimidating heft are much easier to learn on, allowing riders to focus on mastering technique instead of their fear of falling. Additionally, small motorcycles tend to be far less expensive to buy, maintain, and repair than their larger, fancier cousins, especially if not adorned with fragile plastic bodywork.

The downside of entry-level machinery is a function of this same economy. Manufacturers cut costs by equipping such bikes with simple components, like suspensions and brakes that lack cutting-edge technical sophistication or entire feature categories. Noteworthy examples from the past include Honda’s Hawk GT and Suzuki’s SV650, both of which had reasonably peppy, bulletproof motors housed in sweet-handling chasses, held back by budget forks and shocks. Either of these motorcycles could be improved dramatically by just modifying or replacing its suspenders. The same can be said of BMW’s diminutive G 310 R. It’s also better looking than the aforementioned specimens, despite having a motor less than half as large. Having owned and upgraded both Honda and Suzuki models, I recently bought the third of these gems, albeit one with many of its stock limitations already addressed.

I had just sold my last trials bike, which I’d used over the years to hone my off-road skills. I no longer had a mid-sized street bike in my stable and wanted something for parking lot drills—a sort of trials bike for pavement, something easier to learn on and less consequential to drop than my big road burners. I’ve been increasingly conscious of my need for low-speed training and practice. Just as there was more development necessary when transferring lessons from trials bikes to my full-sized dirt bikes, I knew I couldn’t switch from a small street machine to my other road bikes without adjustment. I also knew practicing on a little motorcycle would leave less to master elsewhere, and it wouldn’t involve as much risk of busting costly parts. If I was going small, why not go really small to maximize these advantages?

In the past, that question has been answered by my techno-geek side, which gets queasy about primitive, economical componentry. I’m also an acceleration junky and feel hindered when I have to wait for something to happen after twisting the throttle. But maybe these concerns were less important now; I had other bikes to satisfy my need for speed and hi-tech, and putting around cones wouldn’t make use of advanced technology or breathtaking thrust. I’d buzzed around part of the BMW Performance Center track on a G 310 GS and was surprised to find the motor perky enough to be fun; it also handled quite nicely, though its suspension was rather soft and bouncy. A used one might be inexpensive and suit my current interest well.

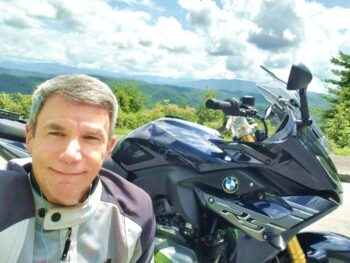

I kept an eye on the local used market for months, and eventually found something I thought might do better than merely meet my minimum requirements. A 2018 G 310 R with less than 5,000 miles had been set up as a track toy, with the OEM pogo sticks replaced by fully adjustable Andreani Misano Evo fork cartridges up front and the shock from a sporty Triumph (Street Triple?) in the back, also featuring rebound and compression clickers. The clunky stock pegs and foot controls had been ditched for sexy items meant for a Kawasaki ZX6-R. The owner had fabricated or substituted a variety of other components as well, frequently using eBay as a source for salvaged or cheaply made parts to minimize his investment. He considered this tiny bike hugely entertaining, but didn’t take it too seriously. It was all about the giggles. When I test rode it, I laughed hard at the incongruities of this Frankenstein’s mini-monster. Most hilarious was its single cylinder’s full-throated exhalation through a no-name exhaust as I banged up through all six gears clutchlessly; an add-on electronic quickshifter (from Healtech) allowed completion of this sequence before I could cover the length of the interstate onramp. Giggles, indeed! Once in the flow of 70+ mph traffic, the high-revving (and effectively counterbalanced) 310 sounded like an angry bee but felt rock solid, as stable as a modern bike three times its size. Then, on a brief excursion through some nearby twisties, it carved corners like a scalpel on rails—a mixed metaphor worthy of this motorcycle’s unnatural juxtapositions. Wide-eyed chortling ensued. Sold! I’d completely forgotten about the intended mission for this purchase.

The original owner’s accounts of online bargain hunting, and his rationale for cheaping out on anything not critical to safety or performance, inspired me. I was shocked at how little salvaged or easily machined parts cost. I’ve quickly spent fortunes on aftermarket mods for most every bike I’ve owned as an adult, but I decided I’d reverse course with this one. I found bargain-basement versions of all my favorite accessories at unbelievably low prices. More giggles. I added a set of slick SW-MOTECH crash bars to further reduce my concerns about dropping the 310 during parking lot drills. These were heavily discounted just because they’d been returned without their packaging—and hadn’t even been installed! Anodized adjustable shorty clutch and brake levers, foot pegs, axle sliders, mirrors, bar-ends, flashing brake lights and grips, all purchased for pennies on the dollar required for their new name-brand counterparts. When the six-year-old (!) battery proved unreliable, I didn’t buy a top-shelf lithium replacement, I got a generic AGM for a small fraction of the expense. When I discovered one of the chain adjustment bolts had broken off inside the swingarm, I didn’t spend $570 for a new piece from BMW, or even a couple hundred for repair at a machine shop—I spent $42 for a pristine salvaged one on eBay, with all the axle and pivot hardware included! The rear ABS sensor died. Purchased new it would’ve been $210, but eBay had it for $60 and it works perfectly. The only thing for which I paid name-brand MSRP was the mounting ring for my SW-MOTECH tank bags. My sides were hurting from all the laughter—until I realized I could have been doing this for many years.

Obviously, I knew people sold used and off-brand parts and accessories more cheaply than new name-brand items, but I didn’t want to slap a bunch of cheap crap on a band new motorcycle. I also didn’t trust the quality of such parts, and I didn’t realize how much cheaper they could be. Sure, the adjustable levers I put on the 310 for $28 (total) are nowhere near as elegantly crafted as the CRG levers I have on another bike ($130 each, many years ago). I wasn’t trying to get “the best;” I wanted the least expensive option that would simply get the job done. It just had to be functional, and if it broke, I could buy it several times over and still come out ahead of what I’d have normally spent. I can lavish my other motorcycles with exotic farkles, the 310 is my mule—and what a fantastic mule it is!

As already mentioned, this machine is a stunning performer. It’s extremely easy to wrap around cones in a parking lot, but it’s also incredible on backroads. I didn’t actually time it, but I may have set my personal best pass of Deal’s Gap on the 310, first time through. I’ve been riding that stretch of road for decades on lots of big-bore sporting hardware, all of which was overkill—for both the tightness of the turns and my own meager riding skills. The 310 doesn’t produce scary acceleration, which is actually helpful, and it makes up for speed between corners with speed in the corners—which is the vast majority of those famed 11 miles. BMW’s engineers did a fantastic job with this chassis; the frame designers must have been so sad to see what the bean counters allowed for the suspension. I’m not saying everyone would be faster on a 310 than a full-fledged sport bike! On cramped serpentine tarmac, though, big horsepower can be more liability than asset, while a little, lightweight, ultra-agile motorcycle can shine very, very brightly.

In terms of smiles per dollar, my 310 is probably the best motorcycling value I’ve ever owned. I couldn’t live with it as my only bike, but it covers a lot of bases. It’s great for commuting, sport riding in the mountains, and skill drills, and it’s comfortable enough to ride for hours on end. It handles local interstates with aplomb, even as I wring its neck to keep up. It sips gas, and its simplicity makes it easy to service, repair, and modify—and it cuts a dashing profile, looking even lighter with its dark wheels, belly pan, and modified rear tire hugger painted white by the previous owner. I wouldn’t want to tour on it, or tote a passenger or luggage, and I’d feel deprived if I couldn’t enjoy more power on another machine, but otherwise the 310 is a surprisingly complete package.

Who knew BMW could produce such a wonderful little motorcycle?—with some help from eBay, that is!

Mark Barnes is a clinical psychologist and motojournalist. To read more of his writings, check out his book Why We Ride: A Psychologist Explains the Motorcyclist’s Mind and the Love Affair Between Rider, Bike and Road, currently available in paperback through Amazon and other retailers.